Growth: Greg Wilson's Account of The Mayaguez Incident

The Mayaguez Incident

Greg "Growth" Wilson, Nail 69

Return to the Kohtang 1975 index or back to the Print News index

Editors Note: “The Growth” was well qualified to be the “Closer” for the Mayaguez Affair. On his first FAC tour he flew 101 missions in Cambodia as an O-1 “Sundog”. He went to the “Raven” program and flew another 504 missions in O-1s, U-17s, and T-28s out of Long Tieng and Pakse.

He returned for a second tour flying Nail OV-10s at NKP, where I

had the pleasure to serve with him in the Tactics, Weapons, and

Training Shop (TWAT).

He returned for a second tour flying Nail OV-10s at NKP, where I

had the pleasure to serve with him in the Tactics, Weapons, and

Training Shop (TWAT).

He flew one more combat mission in Cambodia - “the Last” FAC Combat Sortie in SEA. This is that story.

By 30 April 1975, the U.S. had abandoned both Cambodia and the Republic of Vietnam, President Ford and Secretary of State Kissinger had declared that the war in Southeast Asia was over, and this young FAC captain had long since jettisoned his Air Command and Staff College texts on “force projection in support of national objectives” in protest.

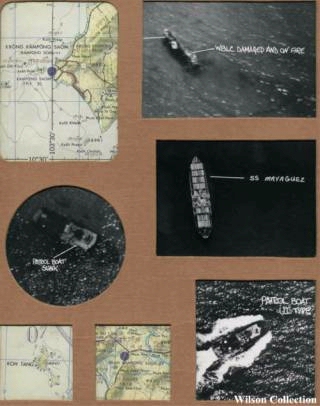

However, not everyone in Southeast Asia got the word that the war was over. Less than two weeks later on 12 May, a flotilla of rogue Khmer Rouge coastal patrol boats detained the US Merchant container ship SS Mayaguez on her normal route from Hong Kong to Sattahip to Singapore. At the time she was in international waters about 60 miles off the coast of Cambodia.

Prior to attacking the Mayaguez, these same gunboats had fired on a South Korean freighter, held a Panamanian freighter captive for 35 hours, and captured over a dozen South Vietnamese and Thai fishing boats.

From the time the Mayaguez sailed from Hong Kong on 7 May until

the Khmers boarded her on 12 May, the captain and crew had received

no warning of these actions. Nor, apparently, had anyone in the US

intelligence community.

From the time the Mayaguez sailed from Hong Kong on 7 May until

the Khmers boarded her on 12 May, the captain and crew had received

no warning of these actions. Nor, apparently, had anyone in the US

intelligence community.

President Ford declared the seizure an act of piracy and demanded the immediate release of the ship and her crew. Over the next three days, in the process of recovering the Mayaguez and her crew, US forces would pay dearly for failed intelligence, poor planning, ineffective command and control, and the lack of dedicated close air support.

The price would be paid with blood in the water and on the sand

of a small island called Koh Tang.

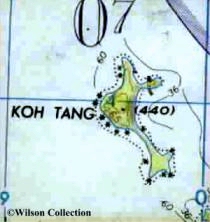

On 13 May, U.S. reconnaissance aircraft located the Mayaguez off the northeast end of Koh Tang, about 30 miles off the Cambodian coast to the southwest of the port of Kampong Som. The ship was kept under intermittent surveillance by a wide variety of airborne platforms ranging from Navy P-3s to Air Force F-111s. At around 7 PM that evening, the 39-man crew was reported being taken off the vessel aboard a fishing boat. People were later observed disembarking from similar vessels at Koh Tang, and intelligence suggested that at least part of the crew was being held there.This was, in fact, an incorrect assessment. It later became painfully obvious that the people landing on Koh Tang were not the civilian crew of the Mayaguez, but Khmer Rouge combatants.

On 14 May, the Commander in Chief Pacific Forces (CinCPAC)

Admiral Noel Gaylor directed the Commander, 7th Fleet

(COMSEVENTHFLT) to prepare forces to support the Mayaguez rescue operation in a three-pronged operation:

1. Storm the Mayaguez, overpower any Khmers on board, and secure her;

2. Execute an amphibious assault on Koh Tang Island and recover the crew;

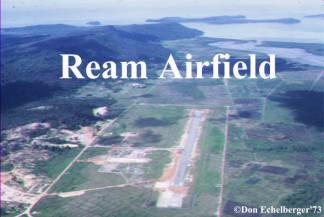

3. Strike military targets in and around Kampong Som airfield (Ream) and Seam Ream naval base to prevent reinforcement from the mainland.

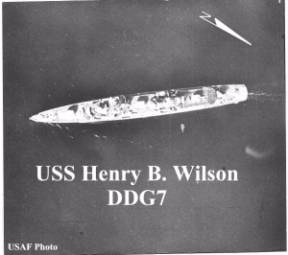

COMSEVENTHFLT, Vice Admiral George P. Steele, directed the aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea and two destroyers, the USS Henry B. Wilson and the USS Harold E. Holt to proceed immediately to the Gulf of Thailand west of Kampong Som and stand by for orders.

CinCPAC designated Lt Gen John J. Burns, commander of the United States Support Activities Group (USSAG) at Nakhon Phanom Air Base (NKP), Thailand, as the on-scene operational commander due to geographic proximity.

Lt Gen Burns, in turn, appointed Col Lloyd Anders, Deputy Commander for Operations, 56th Special Operations Wing (56th SOW) at NKP as the operational task force commander and tasked him to establish a forward operating location at Utapao Air Base, about 200 miles north of Kampong Som.

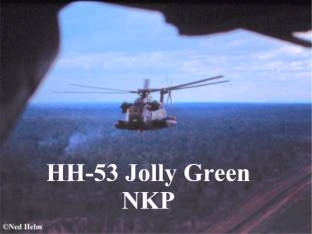

The 56th SOW owned two helicopter squadrons: the “Knives”

of the 21st Special Operations Squadron (21st SOS) and the “Jollies”

of the 40th Air Rescue and Recovery Squadron (40th ARRS). Both

squadrons were equipped with variants of the H-53 heavy lift

helicopter, and Col Anders

deployed them both to Utapao.

deployed them both to Utapao.

Both squadrons had taken part in the evacuation of the U.S. Embassies in Phnom Penh (Operation Eagle Pull) and Saigon (Operation Frequent Wind) within the last month. Although the pilots were predominately 1st and 2nd Lts, they were probably the most experienced El Tees on the planet. They would need every bit of that experience, and more, over the course of the next three days.

Lt Gen Burns also directed 50 members of the 56th Security Police Squadron (56th SPS) to deploy from NKP to Utapao as a contingency assault team. In a harbinger of things to come, one of the “Knife” CH-53s transporting the SPs to Utapao crashed shortly after takeoff from NKP, killing all eighteen SPs and five crewmembers on board.

(Author’s note: A few months prior to this accident, a similar event occurred during a CH-53 Functional Check Flight, the crew. The accident investigation crash found a sleeve or bushing missing from the rotor head assembly shipped from the stateside maintenance depot. This same missing bushing was a primary suspect in this mishap.)

Unknown to Lt Gen Burns, Vice Admiral Steele had already tasked two contingents of Marines (50 from the Philippines and 250 from Okinawa) to execute the assault missions.

Although Col Anders requested the “Nails” of the 23rd Tactical Air Support Squadron (23rd TASS) to support the operation, Lt Gen Burns did not deem Forward Air Controllers (FACs) necessary for this operation and the plan did not include them.

By 14 May, all assigned forces were in place at Utapao. What follows here is the approximate time line of the operation as it played out on 15 May, with personal observations and comments.

0100 hours

The Marine Ground Security Force (GSF), Mayaguez assault team and helicopter crews at Utapao receive a mass mission briefing to include weather, intelligence, call signs and frequencies. While 56th SOW intelligence estimates the enemy force on the island at 15 – 30 irregular troops, the Defense Intelligence Agency estimate is between 100 – 200 regulars. This information is never briefed to the GSF or helicopter crews. Apparently, HQ PACAF does not believe the assault forces have a “need to know”. A set of target area photos is delivered to the assault platoon commander moments before takeoff, but too late to delay the mission or change the hastily developed tactical plan.

0415 hours

Eleven helicopters depart Utapao enroute to their objectives. Jolly’s 11, 12, and 13 proceed directly to the USS Holt with the 50-man Marine assault team and 20 support personnel on board.

Knife 21, 22, 23, and 31 are the first Koh Tang assault wave, followed five minutes in trail by Knife 32, and Jolly’s 41, 42, and 43. The first 180 marines of the planned 250-man GSF are on board the eight helicopters. To provide the element of surprise, the first infill is scheduled for 5:45 AM, five minutes before sunrise. However, the launch order is delayed while President Ford briefs the Congress on the operation, creating a critical 30-minute delay in the time line. The tactical advantage is lost.

0600 hours

The three Jolly’s arrive at the Holt. The landing pad is small and not stressed for the big choppers, forcing each pilot to hover precariously with only the rear landing gear on the Holt’s pad, and off-load their Pax (passengers) via the cargo ramp.

0630 hours

Unknown to anyone in the chain of command, Khmer forces release the captain and crew of the Mayaguez after they are held and interrogated overnight at Kaoh Rong Samloem island, about half way between Koh Tang and Kampong Som. They board a Thai fishing boat for the return trip to their ship.

Almost simultaneously, the first wave of Knives approaches Koh Tang to begin the GSF infill. The plan calls for an insertion into two landing zones (LZs) on the north end of the island. Knife 21 and 22 approach the west beach, followed shortly by Knife 23 and 31 on the east beach.

The West LZ is quiet as Knife 21 makes his initial approach, but with the sun up, and the element of surprise lost he encounters heavy ground fire. With his wingman giving covering fire, Knife 21 stays in the LZ long enough to put his 20 marines ashore. He loses an engine in the process and barely makes it out of the LZ, but he can only manage to “skip” his crippled bird westerly, across the water. On each skip the chopper takes on more water, and after less than a mile it settles into the sea and sinks. One of the crew is lost.

After Knife 22 escorts Knife 21 out to sea, he turns the rescue

of the crew over to Knife 32. Knife 22 makes his run back into the

West LZ, but he also has an engine shot out, aborts out of the LZ

and

limps back to the Thai coastline. The crew and the marine

assault company survive the emergency landing, but the chopper never

flies again. Jolly 11 and 12, who have finished off-loading their Pax on the Holt, pick up the survivors and return them to Utapao.

limps back to the Thai coastline. The crew and the marine

assault company survive the emergency landing, but the chopper never

flies again. Jolly 11 and 12, who have finished off-loading their Pax on the Holt, pick up the survivors and return them to Utapao.

The ground fire in the smaller, foliated West LZ is merely heavy; the East LZ is a large sweeping crescent, which provides the Khmer forces a wide-open field of fire. Knife 23 and 31 are met by a withering crossfire of small arms, heavy machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and mortars, and are both shot down attempting to insert their marines. Knife 23 is relatively intact on impact and is close to the shoreline in shallow water. The 5-man crew and 20 marines make it ashore. They are the first and only forces to reach the East LZ, and despite several aborted rescue attempts, they will be isolated there for over ten hours.

Knife 31 takes a direct hit in a fuel tank from an RPG and disappears in a fireball. The co-pilot is dead, and half the marines are killed trying to reach shore. Eleven marines, including the marine Ground Forward Air Controller (GFAC), and three aircrew survive and swim out to sea under heavy fire from the LZ. They survive for four hours in the water until the Wilson, now on station and proceeding dead slow, spots the survivors by chance, and rescues them.

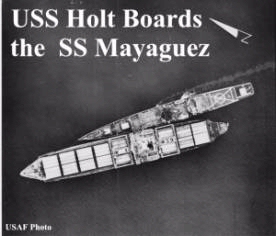

0715 hours

Air Force A-7s from Korat lay down tear gas on the Mayaguez to

incapacitate any Khmers on board,

and the Holt pulls abeam. The

assault team executes a ship-to-ship boarding, the first since 1826.

There is no one on board.

and the Holt pulls abeam. The

assault team executes a ship-to-ship boarding, the first since 1826.

There is no one on board.

0815 hours

Jolly 13, after delivering his Pax to the Holt, is directed to attempt an exfil of the isolated element from the East LZ, but aborts after a minute on the beach. He makes it back to Utapao with heavy damage, and is out of action for the duration of the operation. The first assault, unescorted and with no tactical air support, is a disaster.

(Author’s note: Air Force A-7s at Korat AB picked up the “Sandy” Search and Rescue (SAR) mission following the withdrawal of the venerable A-1 in 1972. Survivor location, helicopter escort, and close air support are primary Sandy roles. However, mission planners do not task them to support the operation.)

0900 hours

The second flight of four helicopters in the first wave fares a little better. There are reasons for this: The East LZ is declared closed and all four choppers make their runs into the West LZ. Also, three of the four helos are Jolly HH-53s and designed for SAR. They are more heavily armored than the Knife CH-53s, with an additional 7.62 MM minigun mounted at the tail of the cargo bay.

They are also air refuelable from HC-130 “King” aircraft, and equipped with 450-gallon, foam-filled external fuel tanks vice the 650-gallon foamless tanks on the CH-53s. In this configuration, they are lighter, more maneuverable, have more on-board firepower, and are less prone to catastrophic fuel explosions like the one that sent Knife 31 into the sea.

(Author’s Note: In yet another planning failure, the HH-53’s were used to conduct the low-threat troop transfer to the Holt. A better plan may have been to use the CH-53s for the troop transfer, and use the more robust HH-53s for the higher threat LZ assaults.)

Jolly 41 makes four unsuccessful attempts to fight his way into the LZ. On the fifth attempt, he gets air support by Spectre 61, an AC-130 gunship. Though he is able to off load only 22 of his 27 marines, this is the first time the assault force has been given any effective air support.

Jolly 42, 43 and Knife 32 insert their marines into the West LZ by 0930. Unfortunately, the GSF command element and mortar platoon are inserted well south of the LZ and are separated by over a kilometer from the main body.

0930 hours

The status of the GSF is grim. Only 130 of the planned 180 marines are on the island, and they are widely separated; there is an isolated element in the East LZ; the command element is separated from the main body in the West LZ by over a kilometer; all are in unfortified positions and under repeated attack by the numerically superior, well-armed and terrain-savvy Khmers. Later, the survivors will describe their feelings of isolation and desolation as they listened to the Khmer soldiers laughing at them in derision.

The status of the helicopter force is worse. Of the eight helicopters in the first wave, all the CH-53s are lost or out of action: Knife 21, 23 and 31 are in the water off the island. Knife 32 is back in Utapao, out of commission for the rest of the operation. Knife 22 is on the Thai coast and will never fly again. The only two operational CH-53s are at Korat Air Base on SAR alert.

The 21st SOS is decimated.

Jolly 41 and 42 have absorbed extensive damage inserting their marines on the West beach and are out of commission at Utapao. Jolly 13, severely damaged in the attempt to pull the survivors off the East LZ, makes it back to the coast of Thailand and remains there for the duration of the operation. Only Jolly 11, 12 and 43 are flyable.

Although the operation has gotten off to a disastrous start, the FACs of the 23rd TASS have yet to be tasked.

(Author’s note: I was stationed with Capt Dick Brasher at RAF Bentwaters in 1980 where we were both flew A-10s. Dick was a former FAC, and at the time of the incident was working in the USSAG command post at NKP. Sometime during the early stages of the operation, he approached Lt Gen Burns and suggested that “maybe we should send some Nails down there to sort things out”. Brasher related that Burns turned on him, stuck a finger in his chest and snarled “Captain, we don’t need any Nails in this operation. We’ve got A-7’s on station, and they’re FAC-qualified!” One can only speculate what the outcome might have been if FACs and A-7 “Sandy’s” had been tasked to support the LZ assaults from the outset.)

Unaware of the day’s activities and not on the flying schedule, I’m relaxing at the Nail Hooch when the phone rings.

“Get your ass to the squadron – NOW!”

When I arrive, Lt Col Ed Maxson, the squadron commander is waiting.

“Pick three guys and take four airplanes to Utapao! There’s a shootin’ war on and there are helicopters down.”

I ask “Only one pilot per airplane?”

Lt Col Maxson confirms, “Only one.”

Apparently, Lt Gen Burns has realized that he has lost over a squadron’s worth of helicopters, and chaos is the order of the day. He has changed his mind, and the Nails have been invited “to sort things out.”

1000 hours

The second assault wave is enroute to Koh Tang from Utapao. Knife 51 and 52 are off SAR alert and the first to get airborne. Of the original eleven aircraft tasked in the first wave, only Jolly 11, 12, and 43 are serviceable. These are the last five flyable helicopters in Thailand.

The plan is to insert all 125 marines on board into the West LZ to reinforce the main body. The assault company, already shot off the West LZ once only to crash in Thailand, is aboard their third helicopter of the day. It has not been a good day for them, but it has been better than the one the marines on the island are having.

Now they’re on their way back to join them.

1015 hours

A Thai fishing boat with 39 Caucasians aboard pulls alongside the Wilson. It is the crew of the Mayaguez, alive and well, although extremely unhappy about being tear-gassed repeatedly by US fighters while enroute from captivity. By late afternoon, they are back aboard the Mayaguez and she is enroute to Sattahip with her original crew and under her own power

1200 hours

Word of the crew’s release reaches Washington, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) send a message:

“Immediately cease all offensive operations against Khmer Republic related to seizure of Mayaguez.”

Gen Burns contacts the Airborne Command and Control Center (ABCCC) and tells the airborne mission commander (AMC) to turn the second assault wave back to Utapao.

At approximately the same time, the GSF commander on Koh Tang queries the AMC on the status of his reinforcements, and is told the second wave has been cancelled. He immediately and aggressively lobbies with the AMC not to abandon him and his marines on the island, but to reinforce them. Col Anders, the operational mission commander is aboard the ABCCC, and weighs in with the GSF. They win their case.

The second assault wave is turned back to Koh Tang, but damage has been done by yet another political delay in the operational timeline. The critical GSF reinforcements will arrive even later than expected, the clock is ticking, and daylight is slipping inexorably away.

In his first situation report, CinCPAC declares “JCS directed immediate cessation of all offensive operations. Accordingly, further strikes were diverted to support the extraction of the GSF from Koh Tang.”

The Mayaguez and her crew have been recovered. The rescue of the GSF is now the order of the day.

The GSF commander decides to consolidate his forces. He, his command element and the mortar platoon are a kilometer southeast of the main body, with only four rifles for perimeter defense among them. The mortar platoon commander crawls forward to a low rise from where he can observe the Khmer positions. Under cover of accurate fire from the mortar platoon, the main body sends a team south to link up with the command element and escort them to the main body. The maneuver is successful and the command element and main body are consolidated.

1400 hours

The second assault wave approaches the West LZ and, again without escort or close air support, each helicopter begins its run. It is Knife 52’s first look at the island and he mistakenly makes his ingress to the East LZ. Caught in the same crossfire that shot down both Knife 23 and 31 earlier in the day, he is lucky to make it out of the LZ and back to Thailand with heavy damage. He is out of action, and his 25 marines never join the battle.

The four remaining choppers, Knife 51 and Jolly 11, 12 and 43 make it into the West LZ and off-load 100 more marines, including the assault company. There are now about 220 marines on the island: 200 in the West LZ and 20 plus the Knife 23 crew of five in the East LZ.

Nail 68, Major Bob Undorf and Nail 47, Capt Rick Roehrkasse launch from Korat Air Base, where they have been deployed for a week. Korat is an hour closer to Koh Tang than NKP, but the two FACs are still two hours away from the action.

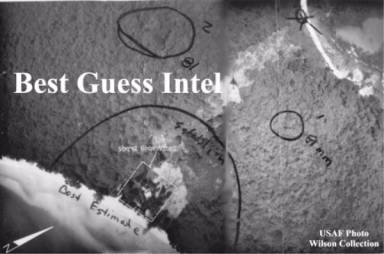

At about the same time, I arrive at Utapao with my flight of four Nails. We go directly to base operations for a briefing on the ground situation, but find the available target materials and intelligence on Koh Tang to be sketchy at best.

The only available maps of the area are 1:1,000,000 scale Operational Navigation Charts left over from a previous OV-10 deployment to Korea. The coastline from Utapao to Koh Tang is depicted, so we can at least find the island. Unfortunately, the island itself is smaller than my thumbnail.

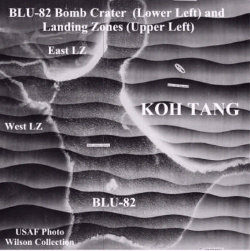

There is a

reconnaissance photograph of the East and West LZs. We are briefed

that there are

helicopters in the water, but no one knows exactly

where. We are given the initial estimate of 15-30 enemy troops on

the island, “but there might be more”. This was, truly, an

understatement.

helicopters in the water, but no one knows exactly

where. We are given the initial estimate of 15-30 enemy troops on

the island, “but there might be more”. This was, truly, an

understatement.

We are told there are marines on the island, but no one knows where or how many. We are briefed on two suspected enemy mortar positions, but those are “just a guesstimate”.

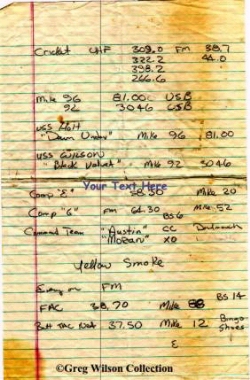

We hastily scribble down the call signs and frequencies for ABCCC, the GSF, and the two destroyers. The GSF consists of a Command Team (Bingo Shoes 6), two companies, and a GFAC (Bingo Shoes 14). The Holt is “Down Under” and the Wilson is “Black Velvet.” Unknown to anyone at the time, the marine GFAC is one of the survivors picked up by the Wilson, and his radios lie useless at the bottom of the Gulf of Thailand.

There are no established code words, but as a contingency

authenticator, we get the GSF commander’s last name and where he

went to school. The thought occurs to me: “Surely a Dartmouth

graduate should be smarter than to end up getting his ass shot off

on some island in the middle of nowhere.”

There are no established code words, but as a contingency

authenticator, we get the GSF commander’s last name and where he

went to school. The thought occurs to me: “Surely a Dartmouth

graduate should be smarter than to end up getting his ass shot off

on some island in the middle of nowhere.”

1415 hours

Jolly 11 and 43 remain in the vicinity of the island after off-loading their marines in the West LZ. Gen Burns, still convinced that unescorted helicopters are a viable option, directs them to attempt yet another exfil of the isolated party in the East LZ. They ingress the LZ with Jolly 43 in the lead and Jolly 11 providing escort with her mini-guns. Again, the attempt is unsuccessful, and Jolly 43 aborts to the USS Coral Sea with heavy damage and streaming fuel, with Jolly 11 in trail.

1530 hours

There are less than four hours of daylight left. The four OV-10s at Utapao are refueled and ready to go. The two FACs from Korat have been airborne about an hour and a half. I try to make my job of picking a wingman easier and tell the other guys that this is strictly a volunteer mission. They all insist on going. I take 1/Lt Will Carroll and we step to our airplanes and launch, leaving the remaining two FACs in reserve. I tell Capt Phil Hofmann to give us a couple of hour’s head start, then launch if they haven’t heard anything else.

The 200-mile flight from Utapao to Koh Tang takes a little over an hour and a half. Will and I are in loose formation at 12,000 – nosebleed altitude for a FAC, but we’re trying to conserve fuel. I am alone with my thoughts.

My father was a “grunt” in World War II and went with Patton on the Relief of Bastogne. He taught me a valuable lesson: “Never walk through a war zone”. I remember his stories of the 9th Air Force P-47s keeping the German tanks and infantry off their backs. I knew then that I would someday fly military airplanes, and that I would keep the bad guys off the grunt’s backs.

No one knows how they’ll react to ground fire until they experience it; it’s the greatest fear of going into combat the first time. My first time was in Cambodia, almost five and a half years earlier, over on old Michelin Rubber plantation east of Phnom Penh. Watching the green .51 cal tracers arcing up from the gun pit in the trees below, the anticipation of first ground fire is instantly replaced by fascination (“Look at that”), an instant later by relief (“Hey, I didn’t choke”), and an instant later by anger (“Those assholes are trying to kill me.”) Then you get on with the business of returning the favor. But in 1970 I was younger – and single. Now I am married, marginally wiser and the same anticipation (Okay - fear) returns. “How will I react to it this time?

On my first tour, I was a “B” FAC - restricted to supporting only indigenous Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian ground forces. Now, for the first time, there are Americans on the ground. And they’re dying. I use this as motivation to replace the “anticipation”.

It’s not Bastogne, but these are American grunts on Koh Tang Island, and they need relief. And it’s my job to keep the bad guys off their backs.

1600 hours

The first FACs arrive on station overhead Koh Tang. Bob Undorf, Nail 68, assumes the role of on-scene commander (OSC). Total chaos has reigned for the last ten hours on, over and around the island, and he must impose order. He is a very busy man. He assigns Nail 47, Rick Roehrkasse, the task of “racking and stacking” available support assets.

For the first time, there is a dedicated OSC on station. Prior to the FACs’ arrival, there was minimum coordination between ground and air forces, and the voice on the radio from above was never the same. With the GFAC out of action, the GSF has improvised and converted the battalion tactical net into the primary strike frequency. Since this is a VHF/FM frequency, and only the Air Force A-7s were equipped with a compatible VHF/FM radio, the OSC duties had fallen de facto to the A-7 flight lead on station at any given time. While this provided some close air support capability, it also resulted in excessive radio traffic on the vital command and control net.

Because the fighters had limited loiter time, there was also very little continuity between the GSF and OSC. Before 1600, OSC duties had changed 14 times between 10 different aircraft. Four of these turnovers had occurred between 0600 and 0700 while the first wave of choppers was being decimated.

Now, for the first time in over ten hours, there is command, control, communication and continuity between air and ground forces, and it is Nail 68 that makes it happen.

His first order of business is the extraction of the isolated team from the East LZ, but to do that he needs to know where they are. Beginning with prominent terrain features and describing those to “Knife 23 Bravo” (2/Lt John Lucas - the co-pilot of Knife 23) on an emergency survival radio frequency, Nail 68 gets a reasonable idea of the friendly position. Time is critical, and he tells the friendlies to keep their heads down as he fires a “Willie Pete” (white phosphorus) marking rocket. The rocket is almost directly on top of their position –too close - and Two-Three Bravo’s strained voice on the radio immediately passes that fact to Nail 68. Fortunately, the small ravine in which the friendlies have spent the past nine hours protects them from the Willie Pete and the Khmers.

1630 hours

Col Anders, aboard the ABCCC (Call sign Cricket), contacts Utapao base operations and tells them to launch the next two FACs. He finds out that Nail 69 and Nail 51 were airborne an hour ago.

Now about 50 miles north of the island, we can see smoke billowing in the distance. Nail 68 has just put his Willy Pete down. Finding the tiny island is a piece of cake.

1700 hours

Will and I check in with

Cricket on UHF 309.0 and copy the tactical frequencies. Black Velvet

is on HF 81.00; Bingo Shoes 6 is on the battalion tactical net, FM

37.50; Nail 47 is marshalling assets on UHF 398.2. We approach the

island and check in with Nail 47. He “pushes” us to Nail 68 on SAR

“Delta”, UHF 282.8.

Will and I check in with

Cricket on UHF 309.0 and copy the tactical frequencies. Black Velvet

is on HF 81.00; Bingo Shoes 6 is on the battalion tactical net, FM

37.50; Nail 47 is marshalling assets on UHF 398.2. We approach the

island and check in with Nail 47. He “pushes” us to Nail 68 on SAR

“Delta”, UHF 282.8.

We switch frequencies, wait for a break in the action and check in, but Nail 68 is a busy man; our presence doesn’t register. On our discrete “B.S.” frequency, I tell Will, “Maintain radio silence and listen up”. We build situational awareness on the battle below. We’re still at 12,000 feet, and I tell Will to pull the power back to “Max Relax” to save even more fuel. I sector the airspace through the center of the island. I have the east side; Will has the west. I “un-synch” the props to make it more difficult for the bad guys to figure out where I’m coming from. The familiar sound of angry hornets fills the cockpit. I trim the airplane a little nose up, and start flying “figure-8s” with the rudder pedals. Altitude, heading and airspeed change constantly, making me a more random target. Old habits.

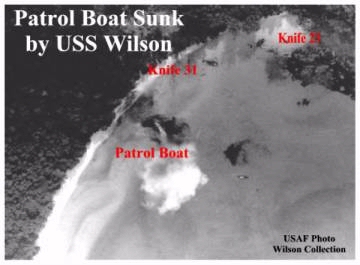

There have been enemy patrol boats in the

area all day. One is sunk in the same cove as Knife 23 and 31, but

about 500 meters farther east of the LZ. Another boat approaches

from the south. Nail 68 asks Black Velvet if she has a “tally” and

she replies “Affirmative.” Nail 68 asks if she can engage the target

with 5-inch gunfire. Again, “Affirmative.” Nail 68 clears the

gun-target line and clears Black Velvet to fire. About two dozen

rounds of direct fire later, the patrol boat is on fire and sinking.

There have been enemy patrol boats in the

area all day. One is sunk in the same cove as Knife 23 and 31, but

about 500 meters farther east of the LZ. Another boat approaches

from the south. Nail 68 asks Black Velvet if she has a “tally” and

she replies “Affirmative.” Nail 68 asks if she can engage the target

with 5-inch gunfire. Again, “Affirmative.” Nail 68 clears the

gun-target line and clears Black Velvet to fire. About two dozen

rounds of direct fire later, the patrol boat is on fire and sinking.

While Nail 68 is dealing with the patrol boat, Nail 47 has been ordering up fighters. With a good tally on the friendlies, they go to work taking down the enemy threat.

Bucktail, a flight of four F-4s, is overhead and low on fuel. Nail 47 hands Bucktail off to Nail 68, who puts a smoke down in the middle of the large supply storage area. Each F-4 makes a single pass, expending all six 500-pound Mk-82 bombs on the target. Bucktail 4 drops short and puts his bombs directly on top of the wreckage of Knife 31.

Spectre 11, an AC-130 gunship is on station, and is the only airborne platform willing and able to employ ordnance in close proximity to the friendlies for the remainder of the mission. Spectre will save the day, and the night.

Black Velvet puts her captain’s gig in the water, armed with four M-60 machine guns. Under command of a chief boatswain’s mate, “Black Velvet 1” will do yeomen’s work for the next three hours.

1730 hours

Jolly 11 has refueled from King 24, the HC-130 SAR mission commander, and has been holding off to the east awaiting clearance to make yet another run into the East LZ to extract the isolated team. He has been on duty since 0100 and airborne since 0415. He is determined to get the people off the East LZ.

Nail 68 has pinpointed one of the enemy positions in a rocky outcropping to the north of the East LZ and asks Spectre 11 if he can engage it with cannon fire within minimum safe distance from the friendlies. Spectre says he can, and does. Jolly 11 calls Nail 68 with a pointed message:

“You see the sun over there on the horizon? It’s going down. We’re the last train out of Dodge for those guys, and we need to get going now.”

Nail 68 gets the message. “OK, you’re cleared in. I’ll cover you.” I try to raise Maj Undorf on the radio and get him to delay until Nail 51 and I can get into position to escort Jolly 11 into the LZ, but we’re too late.

Jolly 11, 1 /Lt Don Backlund, starts his ingress with Nail 68 orbiting overhead, Spectre 11 continuing to pour cannon fire into the outcropping, and Jolly 12 and Knife 51 providing escort. Lt Backlund has been to the LZ before and knows exactly where the 25 men are located. His HH-53 is going flat-out, nearly vertical, the nose of the chopper pointed at the water using the huge rotor blades to literally “swat” the enemy ground fire out of the way. As he approaches the beach, he pulls the nose of the big chopper up, slows his forward momentum, then executes a pedal-turn to put the boarding ramp above the beach directly in front of the ravine where the friendlies are hiding. The wreckage of Knife 23 prevents him from landing on the beach – he must hold the hover with the rear boarding ramp within reach of the survivors.

Several Khmer soldiers charge out of the tree line to attack the now-vulnerable chopper, but they haven’t seen the tail of an HH-53 before. The tail-gunner opens up with his mini-gun and literally cuts the Khmers in half.

Black Velvet 1 runs along the beach, pouring M-60 rounds into the Khmer positions and providing alternative transportation off the beach if needed. The marines and airmen on the island realize this is their last chance. They leave the cover of the small ravine and make a fast but orderly withdrawal to the chopper, firing their weapons to cover each other as they cross the narrow spit of sand.

Nail 68 makes repeated passes on the enemy positions, firing his four 7.62 mm M-60s into the Khmer positions on each pass.

With the survivors aboard, 1/Lt Backlund pulls collective and egresses the LZ, all the while under a constant barrage of hostile fire. All 25 troops finally make it off the East LZ and are taken to the Coral Sea. Jolly 11 has absorbed massive damage and does not fly again. 1/Lt Backlund’s 18-hour day is over. For his efforts he will receive the Air Force Cross.

1800 hours

Throughout the day, there had been reports of a wounded marine still in the wreckage of Knife 23 and Jolly 12 makes an effort to search the wreckage and recover him, if possible. While hovering over the wreckage during a visual search, and even lowering the jungle penetrator into the water and dragging it through the debris, Jolly 11 takes heavy damage. He diverts to the Coral Sea with a wounded crewman and is out of action for the rest of the day.

Black Velvet 1 also moves in close to the beach to search the wreckage, with no success.

In one of the most unexpected events in an already chaotic

day, a C-130 transport arrives unannounced over the island and

delivers a single BLU-82 bomb. The largest conventional bomb in the

world, it weighs 15,000 pounds and is delivered by parachute to

allow the C-130 time to escape the massive blast pattern. It has a

36-inch fuse extender or “daisy cutter” for even greater blast and

fragmentation effect.

In one of the most unexpected events in an already chaotic

day, a C-130 transport arrives unannounced over the island and

delivers a single BLU-82 bomb. The largest conventional bomb in the

world, it weighs 15,000 pounds and is delivered by parachute to

allow the C-130 time to escape the massive blast pattern. It has a

36-inch fuse extender or “daisy cutter” for even greater blast and

fragmentation effect.

Delivered without warning, the blast envelops the island in an outward-expanding shock wave of pressure and water condensation. It flattens every marine who is not in a foxhole. Directly above the island at minimum holding airspeed, my OV-10 is rocked by the blast, and goes into a dive. Potential energy is transformed into kinetic, altitude into airspeed. I recover the airplane and climb back to altitude, wondering, “What the fuck was that?” Remarkably, it eases the tension, like taking your first hit in a football game.

1830 hours

With the East LZ finally evacuated, we turn our attention immediately to the marines on the West LZ, although we have no idea how many of them there might be. To complicate matters, Jolly 11 and 12 are out of action, leaving only Knife 51 to conduct the exfil.

In the first bit of good news in a day filled with bad, the maintenance crews at NKP have generated another HH-53, which launches in mid-afternoon with the call sign Jolly 44. In another marvel of can-do attitude, the flight mechanic aboard Jolly 43 uses a hacksaw, some rubber tubing and a couple clamps from ship’s stores aboard Coral Sea to repair the ruptured fuel line on his battle-damaged bird. It’s not according to the tech order, but the chopper flies.

There are now three helicopters available to exfil the West LZ: Knife 51, Jolly 43, and the recently arrived Jolly 44. On the negative side of the equation, it is getting dark rapidly and there are still 200 marines on the West LZ.

After a magnificent three hours on station, Nails 68 and 47 have run low on fuel and returned to base (RTB). For his efforts, “Undorf the Undaunted” will receive the Silver Star. I assume OSC duties. The darkness belongs to Will Carroll, the chopper crews and me. We have not trained for night operations and we are forced to make it up as we go.

Spectre 11 carries illumination flares, and I ask if he can drop a couple to throw some light on the subject – the dark island below. He immediately complies, but the fuse delays are set too long or Spectre releases them from too low an altitude. The parachutes don’t open, and the flares ignite in the shallow, crystal blue water east of the island.

For the second time, my world is turned upside down. I am used to flying in daylight, but its dark and now my night vision is gone. There is a bright, eerie pulsating blue where the land should be, and pitch black where the sky should be. I have a severe case of vertigo, nearly incapacitated in the cockpit. I can’t talk. Panic sets in.

Fortunately, training takes over. I transition to my flight instruments, head west away from the burning flares, and force myself not to stare at the spectacular light show in the waters below. After an eternity, maybe 10 minutes, the flares burn out. I am perspiring profusely. The sweat smells like copper. I don’t try the “flare tactic” again.

I inventory my assets. Spectre 11 and Black Velvet 1 can provide suppression. Knife 51, and Jollies 43 and 44 are on station to pull the GSF off the beach. I’m in contact with Bingo Shoes (BS) 6, the GSF commander.

Remarkably, no one has advised BS6 that his force is about to be evacuated, but when the first helicopter appears off shore to the west, he and his people are ready to go. The first three exfils are not too difficult. The fading sunlight on the western horizon is behind the choppers as they make their run-in to the West LZ. The troops on the beach can see the inbound helicopters against the horizon.

Unfortunately, so can the Khmers and as the choppers approach the beach the ground fire begins again.

I ask Spectre 11 if he can see

the muzzle flashes to the east of the LZ and he says he can. I clear

him hot with everything he’s got, but to make sure not to

inadvertently engage the return fire from the friendlies in the LZ.

The sensor operators in the back of the AC-130 have an excellent

view of the entire battle on their low light TV (LLTV) and Infrared

(IR) sensors. They take over for Nail 51 and me in directing

Spectre’s cannon fire. Nail 51 reports he is “Bingo” – down to

recovery fuel – and I clear him to RTB.

I ask Spectre 11 if he can see

the muzzle flashes to the east of the LZ and he says he can. I clear

him hot with everything he’s got, but to make sure not to

inadvertently engage the return fire from the friendlies in the LZ.

The sensor operators in the back of the AC-130 have an excellent

view of the entire battle on their low light TV (LLTV) and Infrared

(IR) sensors. They take over for Nail 51 and me in directing

Spectre’s cannon fire. Nail 51 reports he is “Bingo” – down to

recovery fuel – and I clear him to RTB.

Jolly 43, 44 and Knife 51 each pull over 30 marines from the LZ on their first run – 25% more than the Max Pax capacity. Jolly 43 and Knife 51 return to Coral Sea with their troops, but Jolly 44 is inspired. He takes his 34 Pax to the Holt, which is much closer to the LZ and cuts his turnaround time in half. He is the first chopper back into the LZ and pulls out another heavy load in the fading light.

The operation seems to be going well, but this doesn’t last long. The GSF has been reduced by half its manpower, the perimeter defense has pulled back closer to the shoreline, and it is now pitch black.

I hear a transmission from BS6. . “We need to get off the LZ in 15 minutes or we won’t get off at all.” There is small arms fire in the background as he “keys the mike” and an exhausted, desperate urgency in his voice. It is the last transmission anyone will hear from the LZ.

We are cursed by the gods of communication, but receive a gift from the gods of illumination: Someone has put a dim strobe light in the middle of the LZ and I can see it from directly above. The Khmer compound on the East beach is still burning from earlier air strikes, so I have a good east-west reference.

Jolly 43 is the first chopper back from the Coral Sea, and I ask him if he can see the strobe light from off shore. He replies that he cannot. I fly directly over the strobe from east to west and turn on my landing light. Jolly 43 sees the light and takes up an inbound heading.

When my landing light comes on over the beach, the Khmers also take a bead. Ground fire erupts from the island, but Spectre 11 is on the job and returns fire. I find out later that I have flown directly through his gun sight, but the “big sky, little airplane” theory works as advertised.

Jolly 43 is still over a mile from the LZ, and each time I turn back toward the island he loses sight of my landing light. Conversely, the Khmers can see it plainly. I establish the pattern of “Westbound, lights on”; Eastbound, lights off”. Spectre keeps the cannon fire coming; Jolly 43 makes it into the LZ and pulls out another load of marines. (Capt Wayne Purser, the pilot of Jolly 43, will receive the Air Force Cross for his actions.)

My right engine oil pressure begins to drop. I haven’t heard or felt any impacts, but I suspect I may have taken a hit. Leaving is not an option. My grunts are still on the beach.

With no contact with the GSF, I ask Spectre if his guys in back can make out the friendly perimeter. They can, but it has now shrunk all the way to the narrow spit of beach. Knife 51 checks in, and he is unable to see anything on the island. I employ the “landing light tactic” once again and Knife 51 starts inbound. This time I see a large flash to the south and a green starburst illumination flare blossoms over the LZ. Mortar! I later determine that in one of the few pieces of reliable intelligence I received, the mortar tube was exactly where Intel said it was. Not a bad “guesstimate” after all.

I roll in to fire my M-60s, put the “pipper” on the spot where I saw the mortar flash, and squeeze the trigger. Nothing happens – I’ve forgotten to turn on the Master Arm Switch. So much for old habits. My landing light is still on, so I get a good look at the mortar pit, but I’ve been unarmed the whole time. To myself: “Nice fence check, dumb shit!”

Spectre has seen the same flash, and immediately returns fire. Once more I transit his gun-target line, and once more “big sky, little airplane” holds true.

Knife 51 cannot find the LZ through the darkness and the salt spray kicked up by his rotor wash. His spotters tell him to pull up several times when the chopper begins to settle into the water. He finally throws the last vestige of caution to the wind and switches on his landing light. He picks up a tally on the LZ, flies directly inbound, wheels 180 degrees and puts the boarding ramp on the beach.

As the marines come aboard the chopper, one of Knife 51’s crew jumps onto the LZ and sweeps the area for stragglers. This crewman is TSgt Wayne Fisk – a Pararescue Jumper (PJ) and veteran of the Son Tay raid. He is not assigned to the 21st SOS, but has talked his way on board Knife 51 as an auxiliary crewman.

Finding no one left in the LZ, Fisk climbs back aboard the chopper after the last marine, and Knife 51 departs the LZ. He slips on the wet loading ramp and nearly falls out of the accelerating helicopter, but one of the marines pulls him back in. Knife 51 has been in the LZ for another seeming eternity – over ten minutes. 1/Lt Rich Brims, the pilot of Knife 51 - the last flyable CH-53 of the 21st SOS - will receive the Air Force Cross.

I ask Knife 51 to confirm with the marines that everyone is off the LZ and ask Spectre 11 to have his guys in back sweep the area with their sensors. Spectre sees no one. The marine assault company commander, Capt Jim Davis – who finally made it to the island and is the last marine to leave – confirms he has everyone. Knife 51 heads back to Coral Sea with the last marines on board.

have the dark sky over Koh Tang to myself. The island below is even darker. With my right oil pressure needle bouncing off zero, I put Koh Tang behind me and head for home. The Mayaguez Incident and the war in Southeast Asia are over.

In my mission debrief, I offer a scathing critique of the entire debacle, to include the failure to use Forward Air Controllers from the very outset and the decision to send the choppers into the “hot” LZs without escort or close air support.

For my efforts, I am awarded the Air Medal. I am sent home within a month to a non-flying assignment.

Several days after my departure, Admiral Steele, COMSEVENTHFLT, sent a three-page message to the 56th SOW recounting the 23rd TASS contributions to the last combat action in Southeast Asia in detail. He concludes with the following paragraph:

“The outstanding professional performance of ‘Nail 68’ and ‘Nail 69’ in determining the situation existing at the time of their arrival, coordinating and supporting fire and culminating in the successful extraction of the GSF from Koh Tang Island demonstrated outstanding professional competence. Their performance is all the more impressive in light of the severely restricted command and control capabilities existing in their small aircraft and the complexity of the task facing them. The successful completion of the extraction under difficult conditions, finally concluding after dark is testimony to their outstanding performance and positive leadership. There can be no doubt that directly due to their expertise, professional performance, vigilance, tenacity and desire to succeed they were instrumental in successfully recovering the GSF and coincidentally saved the lives of many marines who were extracted. Their performance brings great credit to their service and was in the highest traditions of the United States Armed Forces.”

Four Nails of the 23rd TASS have had a hand in writing the Last Chapter in the War in Southeast Asia. Like all the Nails before us, we kept the bad guys off the backs of the friendlies, and helped bring them safely home.

Epilogue

In the aftermath of the incident, the GSF commander discovered that three of his marines guarding the northern perimeter of the West LZ had been left behind. The Wilson returned to the island the following morning and searched for survivors but, at 10AM, JCS directed all forces to depart Cambodian waters. The three missing marines – Lance Corporal Joseph N. Hargrove, Private First Class Garry Hall, and Private Danny G. Marshall – are left for dead.

Years later, the Joint Task Force for Full Accounting learns that all three marines were alive, captured over the next several days, and executed by the Khmers.

Post Script

The timeline in this article is approximate, at best. For those wishing a more detailed account of the actions leading up to, during, and after the incident, the following reference materials, of which the author has made extensive use, are available (see our Media - Books Page):

US Marines in Vietnam: 1773-1975, “The Bitter End”, Dunham George R. and Quinlan David A., USMC History and Museums Division, Washington, Chapter 13, “Recovery of the SS Mayaguez”,

A Very Short War: The Mayaguez and the Battle of Koh Tang, Guilmartin, John F., Texas A&M University Press.

The Last Battle: The Mayaguez Incident and the End of the Vietnam War, Wetterhahn, Ralph, Carroll and Graf Publishers, Inc.

In Memoriam

My wingman, Will Carroll, fared better than I did in the assignment process. He went back to George AFB, CA to fly the F-105 Thunderchief – “The Last of the Red Hot Mamas”. He was killed in an F-105 crash. I never saw him again,

I met Don Backlund again in 1979 when we were both going through the A-10 Replacement Training Unit (RTU) at Davis Monthan AFB, AZ. We recounted the incidents of 15 March 1975 many times. He was killed in the crash of an A-10, on his next to last RTU sortie.